The blackflies near the river can be something fierce. They are predators whose bites sting. The people in this part of Africa know them all too well. So each day they try their best to avoid the flies as they wait for them to retreat with the sun.

But as night falls, a new menace appears in the skies: the mosquitoes.

Mosquitoes and blackflies are a double threat in these river communities across Africa and other parts of the world. But worse yet are the parasites they carry.

Double threats delivered by day and night

Both Dorothy Kabasimwe and Johnson Bakehahwenki have contracted river blindness and experienced skin irritations. As a result, Dorothy has some vision impairment. Photo: PATH/Lesley Reed.

During the day, a bite from an infected blackfly can transmit parasites that cause onchocerciasis (river blindness), which leads to itching and skin disfigurations, and can induce permanent blindness. At night, the bite of an infected mosquito can transmit parasites that spread lymphatic filariasis (LF). A major cause of elephantiasis, LF is a condition resulting in serious disfigurement and disability.

An estimated 120 million people worldwide are infected with LF, and 37 million have river blindness in Africa. Millions of people living on the African continent are at risk of one or both of these neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). As a group of illnesses, NTDs cause great suffering, adding to a cycle of illness and poverty that disproportionately impacts poor, rural communities across Africa and many remote areas of the world.

Program fatigue: it’s simply exhausting

A health worker sits inside a tent during trials for the SD BIOLINE Onchocerciasis IgG4 rapid test preproduction prototype for diagnosing onchocerciasis (river blindness). Photo: PATH/Dunia Faulx.

The combination of controlling the insects that spread these diseases and mass drug administration (MDA) has been effective at eliminating river blindness and LF parasites from infected communities. This requires persistence, vigilance, and treating the communities annually for years. Communities must be tested regularly to determine when the parasites are no longer a threat. And although multiple rounds of MDA for both river blindness and LF can effectively control parasite levels, if interventions are reduced or stopped before the right time, the diseases can bounce back. This poses a threat to efforts to eliminate both diseases.

Up until now, two separate tests have been used to determine if a person is infected with the parasites that cause LF or river blindness, but they’ve had their drawbacks.

In the case of LF, because the parasites are active in the bloodstream, blood had to be drawn at night by community health workers. And before the Ov16 rapid diagnostic test was developed, people had to undergo an unpleasant process called a skin snip to diagnose river blindness.

“Skin snips and night blood surveys are a burden to communities,” says Dr. Pat Lammie, principal investigator at the NTD Support Center. “Resources for surveillance are extremely limited, and the conventional diagnostic tests used to detect infections in humans are not sensitive.”

Tools to support disease elimination

The new tests will join the SD BIOLINE Onchocerciasis IgG4 rapid test, a monoplex antibody-detection test for river blindness. Photo: PATH/Will Boase.

To address these challenges PATH and Standard Diagnostics (SD)/Alere, a global leader in rapid diagnostics, worked together to develop two new highly sensitive rapid diagnostic tests for both river blindness and LF. These tests are a continuation of PATH’s work to advance new diagnostics to support elimination of NTDs. The antigens used in the new tests were identified and characterized by scientists at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health.

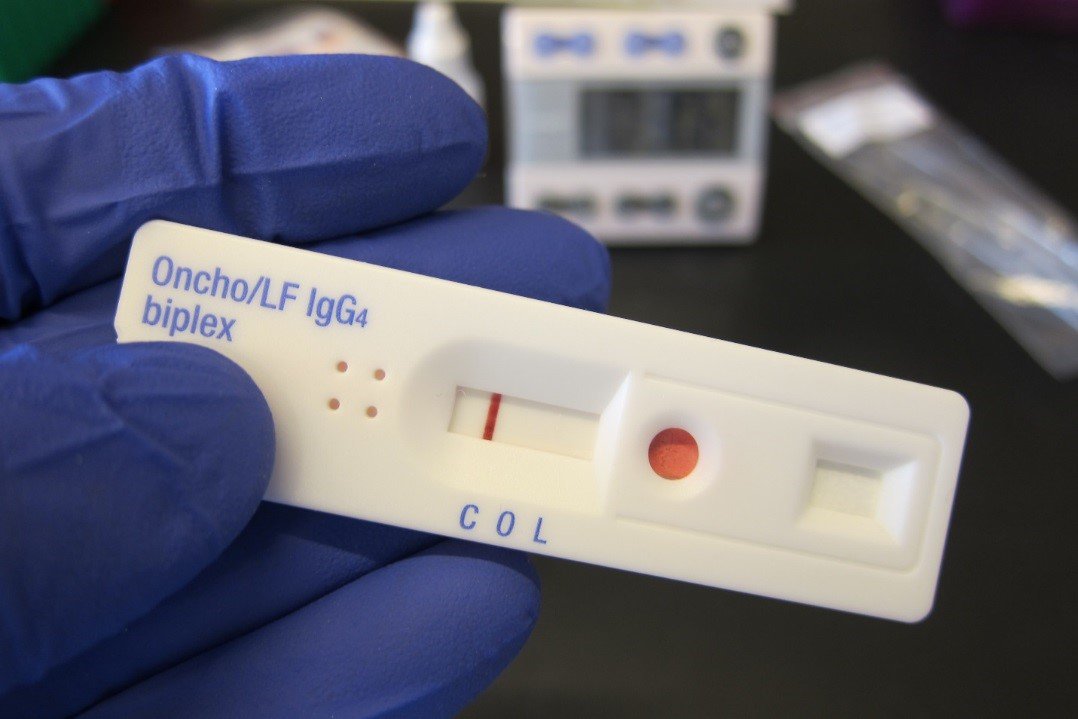

The new SD BIOLINE Onchocerciasis and Lymphatic Filariasis IgG4 biplex rapid test can be used for combined surveillance in coendemic areas of both diseases. Photo: PATH/A. Golden.

The first is a river blindness and LF dual-detection, or “biplex” test, based on the detection of antibodies to parasite antigens for both diseases. It’s designed to fill the gaps in surveillance data for control programs in Africa where both diseases occur. The intent is to provide a new tool to programs monitoring areas that once had these diseases and detecting cases in areas with low prevalence.

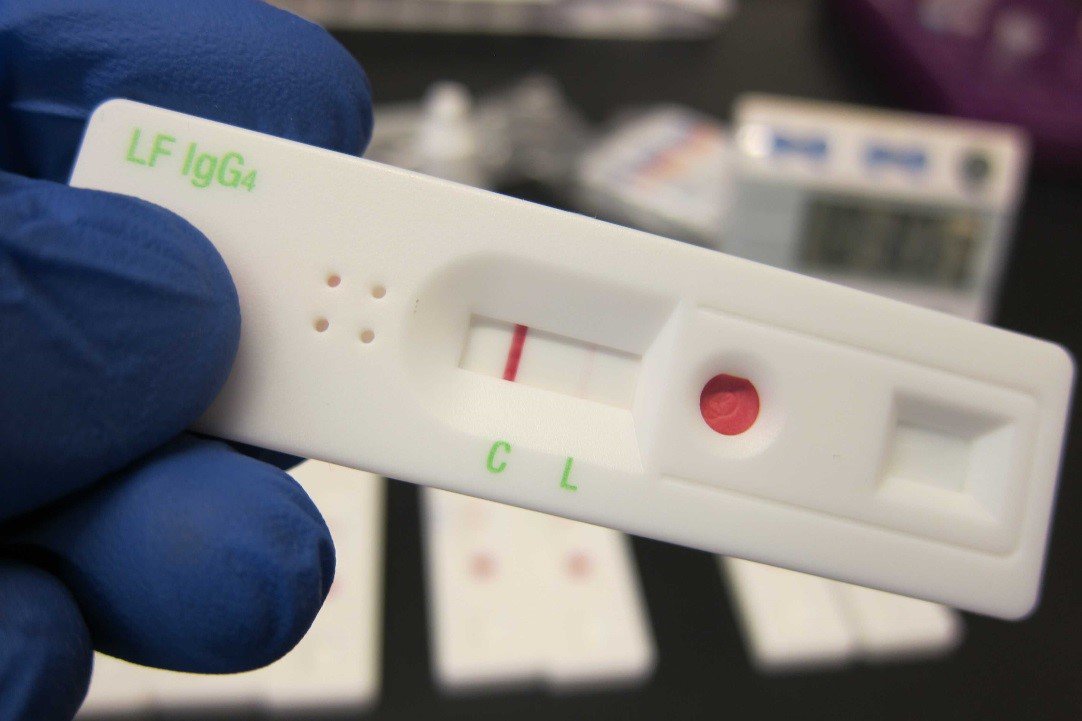

The new LF monoplex test the SD BIOLINE Lymphatic Filariasis IgG4 rapid test, is based on the detection of antibodies to Wb123 for LF alone. Photo: PATH/A. Golden.

The second is a LF monoplex test that can be used in endemic areas where MDA has been ongoing. Here, antibody-detection tests provide important information about recent transmission rates. Data can then be used to make critical decisions about MDA.

“The new tests are game changers,” Dr. Lammie says. “They will empower program managers to make faster and better decisions about their programs, and have ownership over the data that comes from the field surveys.”

Read the PATH blog series on river blindness and our work developing the OV16 diagnostic test

They’ll make a difference in how surveillance strategies are conducted at the country level, too. “Reducing or stopping MDA is an important public health decision,” says Professor David Molyneux, NTDs lead at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. “These tests should be combined with entomological surveys to prove that countries have achieved their goals of arresting transmission.”

So those blackflies and mosquitoes better be on the lookout.

The road to elimination

The World Health Organization has targeted LF for global elimination and river blindness for elimination in select countries in Africa by 2020. At PATH, we’re working with our partners in the NTD community to develop tools that will help make that a reality for the people affected by these diseases.

Funding for the development of the onchocerciasis and LF biplex and LF monoplex tests was provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.