Refrigeration is crucial to protect the potency of many vaccines, including those against COVID-19. From global transport through local delivery, a comprehensive cold chain system is critical to maintaining the 2°C to 8°C temperature range these vaccines require.

Dozens of common drugs—including injectable or liquid medications like insulin, many antibiotics, biologics, and more—also require cold or cool storage. As with vaccines, specialized technologies and training on insulation, cooling, and systems monitoring are important to safeguard these pharmaceuticals. But while substantial investments over the last several decades have strengthened the cold chain for vaccines, the systems and capacity for essential medicines have not seen such investment.

“In countries where PATH works, there is a significant deficit in access to essential drugs and other temperature-sensitive health care products,” says Jaclyn Delarosa, Program Officer in the Medical Devices and Health Technologies program. “Many countries still struggle to maintain a consistent supply of medicine.”

Integrating vaccines and essential medicines

Deficits in cold storage facilities are most significant in rural areas, which Delarosa says can be particularly problematic, “as medicines often have a slower, longer, and riskier journey in the cold chain to reach them.”

In Myanmar, for example, PATH found that less than half (44 percent) of rural health facilities have any cold chain system while the vast majority (90 percent) of health facilities in urban areas do.

We need more resources and investments to strengthen and expand the cold chains for both medicines and vaccines, especially in rural areas. However, in cases where resources remain limited, integrating essential medicines into the vaccine cold chain could offer opportunities to address supply bottlenecks and improve health outcomes.

To analyze the feasibility of integration, PATH reviewed cold chain systems at more than 13,000 facilities across nine countries—Central African Republic, Ghana, Haiti, Laos, Kenya, Myanmar, Sudan, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

The findings suggested that many countries lack systems and storage capacity for medicines. And while most clinics did not have space for integrating essential medicines into the vaccine cold chain, some facilities did have excess storage capacity in the vaccine cold chain.

This points to some untapped potential in the vaccine cold chain, which could be leveraged to safely transport and store more essential medicines in communities that need them.

Furthermore, global guidance has recently evolved to support integration where possible.

Historically, global guidance advised clinics to maintain separate cold chains for vaccines and medicines, but in late 2020, as new vaccines and therapeutics against COVID-19 caused demand for cold chain capacity to surge, UNICEF and the World Heath Organization encouraged “greater health commodity supply chain integration for temperature-sensitive pharmaceuticals where appropriate.”

This expanded on a 2015 statement that advised including temperature-sensitive products such as oxytocin within the vaccine cold chain where feasible, cost-effective, and managed according to best practices.

Guidelines at the national level, however, still often require or assume separate storage for vaccines and medicines.

Managing risk for safe, effective integration

In order to safely and effectively integrate the vaccines and essential medicine cold chains, it will be critical to adopt and implement the new global guidance, which includes important safety policies and practices.

Implementing these safety standards will require significant investment in health worker training, protocol development, and equipment upgrades to ensure integration is carried out safely and effectively. Without protocols and guidance, integration could cause confusion, inaccuracies, and even life-threatening consequences.

PATH is helping review capacity and develop protocols for cold chain integration in the countries where we work. With investments that strengthen systems and thoughtful, strategic health worker training, integration can offer a cost-effective solution that improves the health of communities.

To manage clinical risk, essential requirements for safe and effective cold chain integration include:

- Simple and uniform visual indicators on product labels, packaging, and designated storage areas within refrigeration equipment.

- Training curricula, standard operating procedures, manuals, and monitoring systems.

- Specialized training on products to be integrated, including processes for detecting, reporting, and documenting unanticipated problems.

- Clearly defined roles for health workers, particularly those working across different clinical departments.

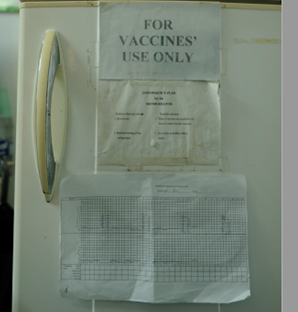

Many rural health facilities in low- and middle-income countries often have only one refrigerator for storing vaccines and essential medicines. Photo: PATH.

Building on immunization investments

In Ghana, untapped capacity is already poised for careful integration.

Last year, PATH reviewed vaccine cold chain capacity at more than 700 public health facilities in Ghana, each serving a population of less than 10,000. We found that 87 percent of vaccine storage went unused.

PATH estimated that total cold chain capacity would need to increase by only 30 percent in order to integrate cold storage of oxytocin, insulin, and rabies prophylaxis within Ghana’s vaccine cold chain.

“By validating the capacity levels and piloting the entire process of integration in one municipality in Ghana, we have an opportunity for Ghana’s health leaders to leverage our efforts and expand access to lifesaving temperature-sensitive pharmaceuticals,” says Dr. George Amofah, Technical Advisor to the Access Accelerated partnership, Non-communicable Diseases Project, in Ghana.

Prioritizing medicines alongside vaccines in the cold chain system could create immediate impact, in Ghana and for communities around the world. This will require investment in integration that combines vaccines and medicines, along with safety standards and policies, careful planning, training, and quality data.

Effective and efficient cold chain integration, when implemented, reduces stockouts of lifesaving medicines, improves health service delivery, and can be an important strategy to overcome service disruptions in lifesaving care.