Until recently, genome sequencing has been limited to specialized centers outfitted with expensive, industrial-scale equipment—and the staff and budgets to maintain it.

But now there’s a new kid on the block: nanopore sequencing. This technology, packed into a device called a MinION, is so small and portable that it can “read” complex strings of RNA or DNA with just a laptop—no specialist lab required. With a MinION, a researcher can perform sequencing almost anywhere. And the price is appealing: a nanopore starter pack comes in at just $1,000.

As PATH’s Dr. Dan Bridges explains, this new technology means scientists in under-resourced settings can perform genome sequencing themselves, own the resulting data, and drive the subsequent research. “Nanopore is helping us build capacity and be independent from out-of-country labs,” says the biochemist of his team at the National Malaria Elimination Centre in Zambia. “This technology allows Zambia to develop its own genetic capabilities in-house.”

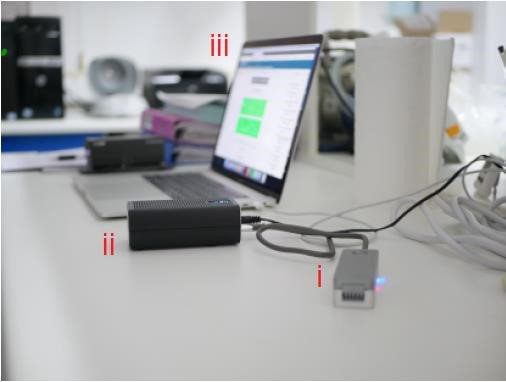

The nanopore sequencing setup in Zambia’s National Malaria Elimination Centre consists of three parts: i = the MinION device, ii = MinIT (optional controller that aids sequence analysis), iii = laptop to view results. Photo: Oxford University/George Busby

Tracking COVID-19’s genetic trail

Last year, Zambia’s National Malaria Elimination Centre hosted experts from the Mobile Malaria Project who trained the PATH lab to perform independent nanopore sequencing of malaria parasites. The goal: define the parasites’ drug resistance profile. Thanks to the team’s success, plus PATH’s strong partnership with Zambia’s Ministry of Health, the lab recently won a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to continue this work.

The PATH team will also apply its experience to SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing. Although the infection rate in Zambia remains low (fewer than 200 confirmed cases as of mid-May), sequencing could play a crucial role in tracking COVID-19 and informing the country’s response.

Tiny mutations naturally occur as the virus replicates. By tracking these as SARS-CoV-2 moves from one human host to the next, PATH scientists will search for sources of infections and links between them. Nanopore sequencing may help them to see where cases originate and how they’re spreading.

This Nextstrain chart displays the evolutionary history of the SARS-CoV-2 virus as it has mutated and spread over time. Image: Nextstrain.

“We’ll look for clustering and common ancestors,” says Mulenga Mwenda-Chimfwembe, a scientist in the lab. “The mutation rate may help us infer how many people are in a chain of infection.” The process can also clear up confusion that can arise in traditional contact tracing, by linking apparently unrelated infections to a common source.

All hands on deck

Genome sequencing is just one aspect of PATH’s response to COVID-19 in Zambia. “The scenes in other countries are chilling,” says communication and policy team leader Todd Jennings. “It’s an all-hands-on-deck situation here.” PATH is participating in virtual forums with decision-makers and partnering with the Ministry of Health to facilitate equipment donations, data collection, and media coverage.

Even in the midst of pandemic, the fight against malaria remains top of mind. To date, there have been fewer than ten confirmed deaths in Zambia due to COVID-19. But malaria kills, on average, four Zambians every day. “Malaria testing must continue,” says Todd, “but it must be safe for everyone—including the community health workers who administer the tests at the household level.” PATH is contributing to global and local guidance on malaria programming in the context of COVID-19, developing messages and materials to support some 12,000 trained community health workers.

“No one knows how this virus will play out in Zambia,” says Todd. “The times are uncertain and scary, but it’s also heartening to see how quickly individuals and organizations are mobilizing around a common goal. We are proud to be a part of the effort.”