Conventional vaccination methods require a needle and syringe to deliver “shots” into the tissue under the skin or deep into the muscle. But delivering shots to the skin itself can be just as effective at generating an immune response, and it can be a lot easier to access, too—potentially helping immunization programs to address coverage gaps and reach even more children.

PATH’s Darin Zehrung, portfolio leader for Vaccine and Pharmaceutical Delivery Technologies, answers our questions about skin vaccination (the delivery of vaccine to the upper layers of the skin) and what makes it so important.

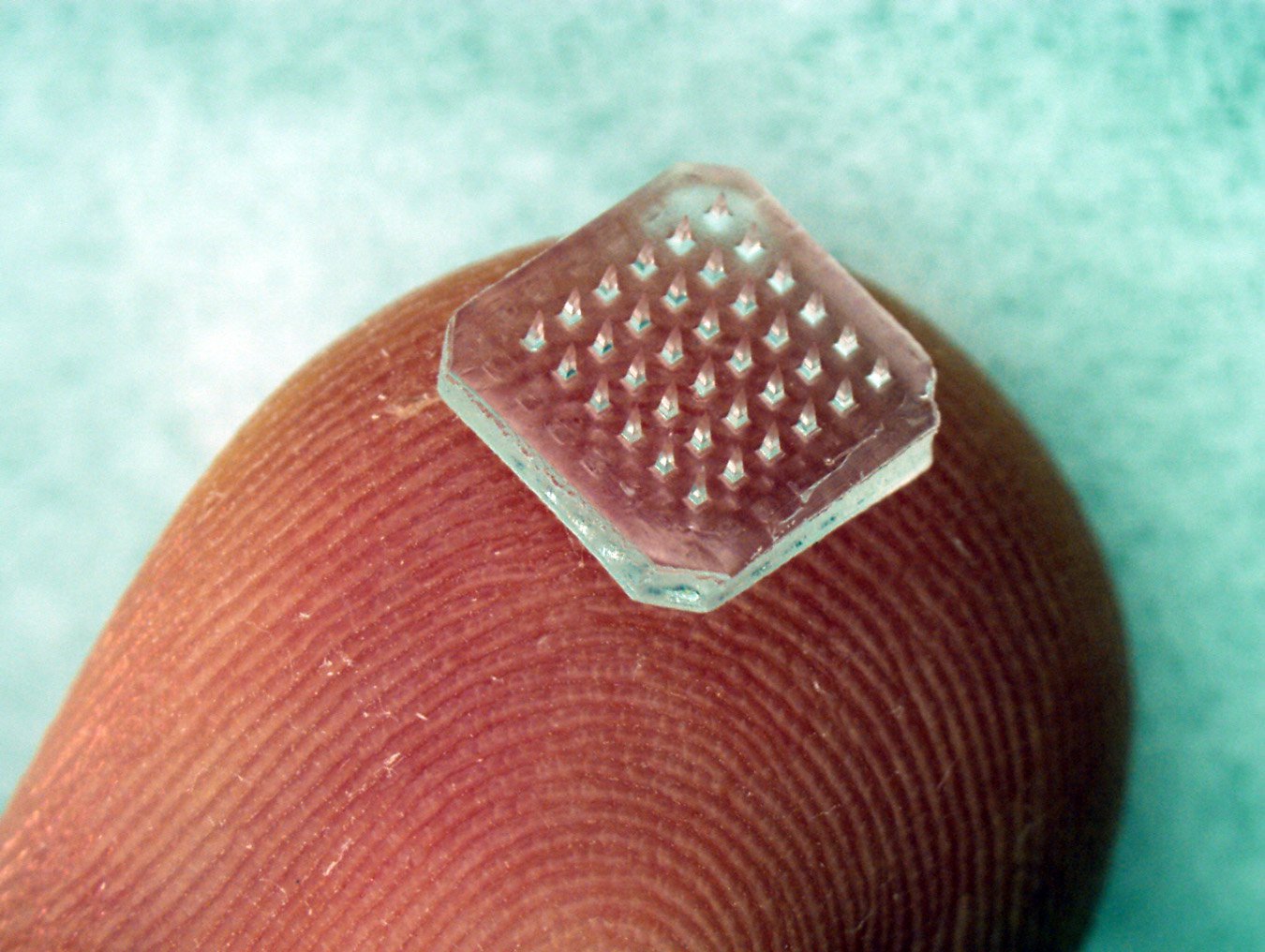

A patch containing dissolving microneedles is shown on a fingertip. The microneedles dissolve within minutes into the skin to release the vaccine. Photo: Jeong-Woo Lee/Georgia Institute of Technology.

Q: Besides lowering the “ouch!” factor, what makes skin vaccination so exciting?

A: The reduction or total elimination of needlestick injury and sharps waste may soon be possible with skin vaccination technologies that are needle-free or use dissolvable microneedle patches. Additional advantages potentially include more efficient packaging, fewer training requirements, and an increased number of people vaccinated in the remote clinic or campaign settings most common to low- and middle-income countries.

But we hope to take it one step further. Families in developing countries often travel many miles on foot to access vaccines. Imagine minimally trained health care workers or volunteers going door-to-door in remote villages, administering painless and dissolvable vaccine patches that adhere to patients like Band-Aids. Such outreach strategies could be game-changing for measles elimination and polio eradication, among other efforts.

Darin Zehrung. Photo: PATH/Patrick McKern.

Q. How else is skin vaccination different—or better—than conventional vaccination?

A: All vaccines lose potency over time. As the rate of loss is temperature-dependent, the World Health Organization recommends vaccine products be transported and stored between 2°C to 8°C to maintain their potency prior to delivery. This requires a temperature-controlled cold chain, which can be difficult to sustain in low-resource settings. Skin-delivered vaccine formulations can potentially be more thermostable than injectable vaccines, helping to ensure patients receive fully potent vaccines even after the vaccines have been exposed to temperature extremes.

For some vaccines, skin vaccination may also decrease the amount of antigen needed to achieve immunization. This could help reduce costs for immunization programs by increasing the number of doses produced from a given quantity of vaccine; however, effects of this so-called dose-sparing method on affordability are still being assessed.

Q. Are skin-delivered vaccines as effective as injectable vaccines?

A: Yes, for some vaccines, and knowledge of this fact is not new. In 1796, Edward Jenner leveraged skin vaccination to prove that people could be inoculated against smallpox by scratching pus taken from blisters of a cowpox-infected person into the skin of an uninfected person. Today, more sophisticated skin vaccination methods can achieve the same result—stimulating the dendritic cells in the skin to efficiently deliver vaccine to the lymphatic system where antibody and T-cell immune responses take place.

Q. What drives your work in skin vaccination?

A: I came to PATH 17 years ago to help develop safe-injection technologies. Since then, our work has expanded to include developing novel skin-delivery systems. These efforts directly align with the World Health Organization’s Global Vaccine Action Plan, which aims to expand vaccine access and delivery, especially for the one in five children worldwide who aren’t immunized.

Q. What is PATH doing to advance skin vaccination?

A: PATH led the development of the intradermal adapter, an injection-aid device that fits over traditional needles like a sleeve and helps health care workers to successfully deliver an injection into the top layers of the skin. We’ve also worked on other needle-free delivery devices, including disposable-syringe jet injectors that are also capable of administering intradermal injections.

More recently, we’ve been helping to develop dissolvable microneedle patches. These patches have the potential to save immunization programs money because their small size makes them cheaper to store and transport. Patches are also easier to use, so much so that self-administration may be possible—something we’re exploring in collaboration with Emory University and the Georgia Institute of Technology. People may be more willing to wear a vaccine patch on their arm for a few minutes than go to a clinic for an injection. We’re also assessing how the delivery route can be leveraged for essential medicines, including the delivery of antibiotics to newborns.

Q. When will these technologies be available for immunization programs?

A: Some, like the intradermal adapter, could be available very soon. Other technologies in development have much more work to be done to ensure they are safe, effective, and acceptable to users. But, innovations in skin vaccination hold a great deal of promise. They could dramatically increase vaccine access and delivery worldwide, and that inspires me.

Darin Zehrung leads PATH’s Devices and Tools Program. Prior to becoming the leader of Devices and Tools Program in 2018, Mr. Zehrung led PATH’s portfolio in vaccine and pharmaceutical delivery technologies, helping position PATH as a globally recognized expert in delivery and packaging technologies for vaccines and essential medicines.