In 2014, countries worldwide signed on to 90-90-90 goals that, by end of 2020, would result in diagnosing 90 percent of all HIV-positive people, providing antiretroviral therapy (ART) for 90 percent of those diagnosed, and achieving viral suppression for 90 percent of those on treatment.

As the 90-90-90 deadline draws closer, PATH and partners are measuring our progress in epidemic control and defining what needs to be done in the next five and ten years to dramatically accelerate progress towards the 2030 goal of ending AIDS.

Namibia, Cambodia, and New York City have all achieved and surpassed the 90-90-90 goals for HIV diagnosis, ART enrollment, and viral suppression. Key to their success: the decentralization and differentiation of treatment services. By adapting the ways in which they prescribe and dispense ART, health and community leaders in these localities have made it easier for people living with HIV to access treatment and remain in care.

These models allow for patients to collect their medicines every three to six months, and to do so through community-led groups, or through fast-track mechanisms at clinics. Some countries allow for drugs to be home-delivered or sent in the mail, while others are making ART available through vending machines. A number of countries—low-, middle-, and high-income—have put these strategies in place, and to great success. ART retention and viral suppression rates equal or surpass what is seen in clinic-only models.

These approaches, known as differentiated care, are at their core about trusting people living with HIV and focus on discerning what best enables access to services. They are the answer to questions such as: why are there high loss to follow-up rates among those receiving treatment at health facilities? How can user insights generate solutions that put them first and enable greater ease in starting and continuing treatment? This approach disrupts traditional hierarchies and paradigms, shifting the focus to community-led treatment and self-care.

PATH plays an active role in this critical movement, supporting an array of community-based ART services across the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, and Vietnam. By tailoring treatment plans to local preferences, differentiated care has resulted in retention and viral suppression of more than 90 percent among people living with HIV that participate in these programs.

A couple in the Democratic Republic of the Congo pick up their three-month supply of medication at a community treatment distribution point. PATH/Didier Kamerhe.

These decentralized models of ART distribution and care have driven such strong results that they now form the basis for additional service delivery. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, local health authorities now integrate tuberculosis preventive therapy into community-based ART services. In Kenya, family planning counseling has been integrated into fast track community facility ART dispensing.

How have differentiated care approaches informed HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis service models?

The World Health Organization recommended oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—two antiretroviral medicines that when taken as prescribed are as high as 99 percent effective in preventing HIV—as an option for select populations in 2012, and then in 2015 for all individuals at substantial risk of acquiring the disease.

Despite the diversity of models and creativity in how ART is now delivered, PrEP services remain more uniform. Most PrEP services in low- and middle-income countries are offered at government-run health facilities or through private services. Services are clinic-based and require otherwise healthy individuals to come to them around six times, and sometimes more, in the first year.

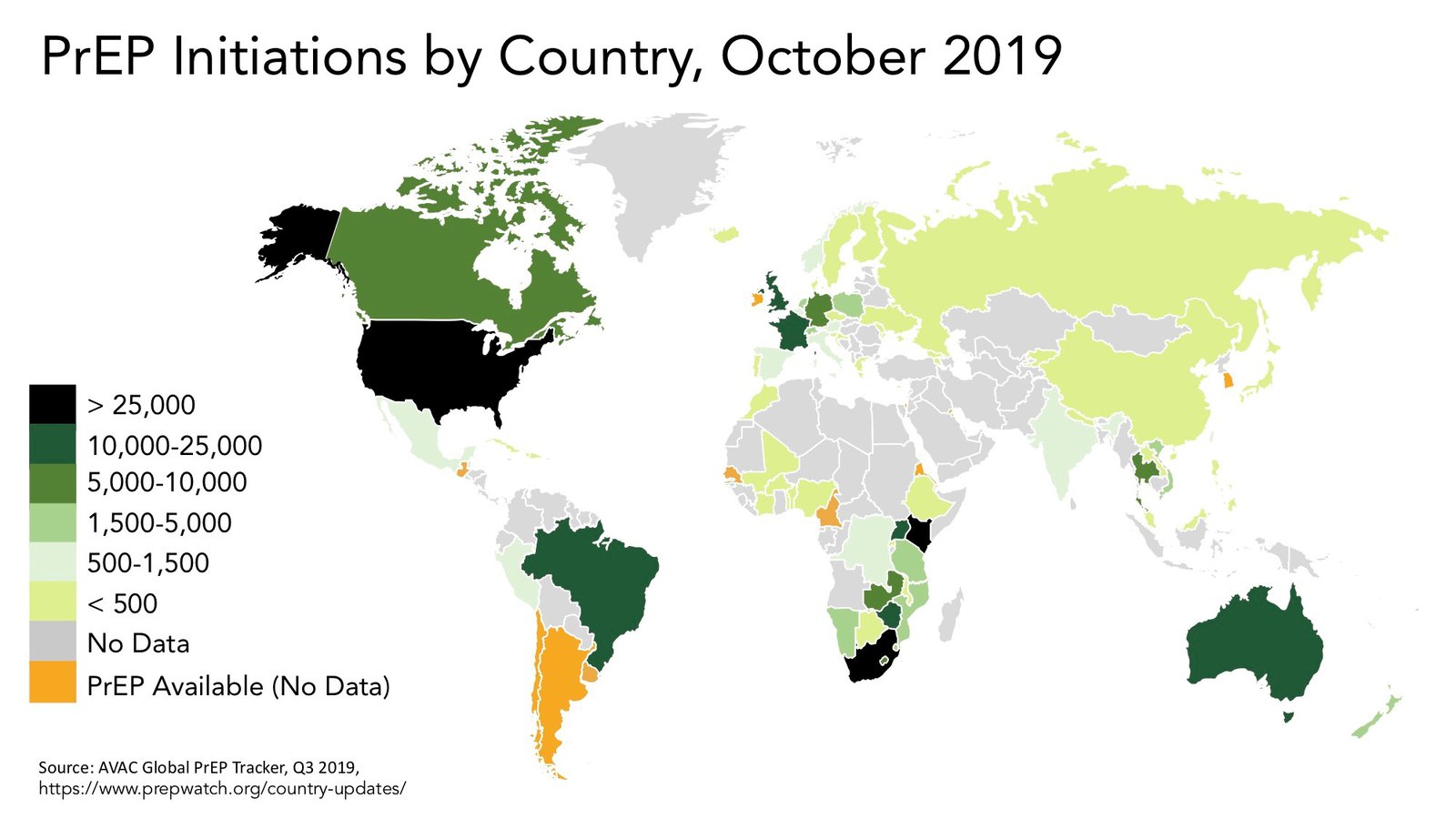

PrEP had a slow start in many parts of Africa and Asia, in part because of financing uncertainties and stigma associated with PrEP. Health leaders also expressed concerns about how to offer PrEP and to whom, and were largely cautious in roll out. But the pace of adoption and use is increasing; there are now at least 75 countries offering PrEP, with an estimated 380,000 people currently using the preventative therapy worldwide. Most of these (58 percent) reside in three countries: the United States (130,000), Kenya (55,000), and South Africa (34,000).

As of October 2019 the majority of PrEP users are concentrated in Kenya, South Africa, and the United States. Map courtesy of AVAC.

Even as the number of people starting PrEP increases, there are real challenges with enabling clients to stay on the drugs. Kenya has been hampered by very high drop-out rates among adolescent girls, young women, and other populations. After six months, only 15 percent of those who start on PrEP remain on it.

What do PrEP users really want?

Studies in several countries have found that PrEP users want accessing the service to be easy and convenient. In Vietnam, a PATH-led assessment among transgender women and men who have sex with men found that 71 percent wanted to receive PrEP through a community-based organization. PrEP is now being offered by community-led and owned clinics (though not yet dispensed in nonclinical settings). In Malawi, female sex workers preferred to access PrEP through family planning services or drop-in centers.

In the United States, to overcome stigma from health workers, the city of Seattle offers "One-Step PrEP" through pharmacies, and the state of California has now embraced this approach by offering PrEP (and post-exposure prophylaxis or PEP) over the counter, no prescription required. On the other side of the country in Florida, a mobile van distributes PrEP to migrant populations that had not previously had access to HIV services.

In Australia, community clinics offer PrEP through nurses to increase access and availability. In the United Kingdom and elsewhere, gay men and others who want PrEP seek it through online mail order and monitor themselves through local clinics or self-testing.

Since the ECHO trial results, more PrEP programs in Africa are looking to integrate PrEP into family planning services. Kenya has led the way in terms of diversity of PrEP locations, which include family planning, maternal and child health clinics, ART clinics, HIV testing services, safe spaces for adolescent girls, and drop-in centers for key populations.

And speaking of family planning, learning from the method-mix approach and over-the-counter access to contraception has paved the way for increased use and sustained a myriad of improved health outcomes for women around the world. The focus on method choice and access were critical to enabling a dramatic increase in uptake of modern contraceptive tools.

To rapidly increase access to and uptake of PrEP, we have an incredible opportunity to reduce the time to innovation. How? By adapting approaches used in differentiated care for ART, and family planning services, to establish community-based and -led PrEP models that best respond to the preferences articulated by HIV-affected populations.

This could include PrEP dispensing from community-based organizations and peers (who in many countries have already been trained as lay HIV testers and/or distribute HIV self-tests and could offer quarterly HIV status monitoring for PrEP users). It could also include home delivery, by peer or by mail, and online follow-up as needed from a trained clinician. For young people, data indicate that creatinine measurement may not be necessary; many countries in Africa have removed this requirement to simplify access. For sexually transmitted infections, self-sampling, mobile clinics, and improved quality and cost of clinic-based testing and treatment could and should be offered at a much larger scale. This should include exploring pooled sampling for chlamydia and gonorrhea which are often asymptomatic. And among HIV serodiscordant couples, offering PrEP to the HIV-negative partner through a community ART or refill group would be ideal, as it would align ART and PrEP service delivery and simplify access for couples.

Key population-led community clinics, like Glink in Vietnam, offer greater choice when it comes to PrEP. Photo: PATH Vietnam.

Back to the future

Sometimes the innovation we need comes from something in the past that can be adapted for a new purpose. Learning from differentiated treatment, listening to what people want, and trusting them are how we enable those who could benefit from PrEP to access it and feel in control of how and when they can start and stop depending on perceived need and their seasons of risk.

With event-driven PrEP for men who have sex with men, and long-acting PrEP, we have an opportunity now to lay the foundation for easier access to PrEP in the community, at pharmacies, online, or in public or private clinics.

Ultimately, by democratizing PrEP access and uptake through differentiated, community-based models, we will truly be able to accelerate use, and achieve dramatic and durable population-level reductions in HIV.